Opinions and analyses on US and global security presented by H. Ross Kawamura: a foreign policy commentator; an advocate for liberal interventionism and robust defense policy; a watchful guardian of a world order led by the USA, Europe, and Japan.

Monday, October 02, 2023

The question of Britain’s tilt to the Indo Pacific and its relationship with China

Britain is one of the key partners of the multilateral coalition to enforce FOIP operations to defend the rule of law in the Indo-Pacific region, particularly in view of maritime challenges by China. Ever since the Johnson administration released the Integrated Review of Security, Defence, Development and Foreign Policy entitled “Global Britain in a competitive age” in March 2021, the United Kingdom has been proceeding strategic tilt to the Indo Pacific. In accordance with this strategy, Britain is deepening strategic partnership with Japan and India. Particularly with Japan, Britain signed the RAA (Reciprocal Access Agreement) this year to faciilitate access to mutual troop facilities and bilateral operational and training cooperation between their armed forces. Also, both countries conduct joint research and development of the GCAP (Global Combat Air Programme) with Italy. With India, Britain provides technological assistance for its indigenous next fighter project to supplant Russian sponsored FGFA (Fifth Generation Fighter Aircraft). Furthermore, the United Kingdom singed the AUKUS deal with the United States and Australia. In view of those agreements, Britain is supposed to be deeply committed to the FOIP against China along with regional powers like Japan, India, and Australia, and most importantly, through the “special relationship” with America. However, some restraints of domestic politics, notably the Labour Party and the financial lobby, could erode Britain’s solid commitment to the deterrence against China. Also, the Sunak administration is not necessarily harmonious in their stances against China, unlike their approaches against Russia.

Let me mention the Labour Party first. Shadow Defence Secretary John Healey questioned Tory national security strategy of the tilt to the Indo Pacific initiated by the Johnson administration, in view of growing threat of Russia since the outbreak of the ongoing war in Ukraine. Secretary Healey said that Britain should focus its limited budgetary resource on the defense of its home turf and the Euro Atlantic, as commented "The first priority for Britain's armed forces must be where the threats are greatest, not where the business opportunities lie” (“Labour defence chief questions using UK's 'scarce resources' in Indo-Pacific”; Forces Net; 8 February, 2023). The point of Labour argument is that Britain should rearm to meet the requirement to defend Europe, the Atlantic and the Arctic, while its military stockpile at home is depleting to support Ukraine (“Labour calls for UK rearmament and end to military cuts”; UK Defence Journal; February 7, 2023). But does the Labour Party belittle the threat of China, although it encroaches Britain’s homeland via secret agents, cyber manipulations, etc? Current party leader Keir Starmer assumes himself a Blairite, but his party’s defense initiative seems more like Harold Wilson’s who decided to withdraw British troops from east of Aden in 1968, rather than Tony Blair’s whose global trotting foreign policy explored to let Britain punch above its weight.

If the Labour Party is not obsessed with anti-colonialist woke ideology, how would they strike a balance between Britain’s strategic necessity around the globe? Rather than denying the tilt to the Indo Pacific, Veerle Nouwens of the RUSI (Royal United Services Institute) suggests that the Labour Party tailor the tilt to their priorities. Geographical distance is no reason to disengage from the Indo Pacific. After all, the Tory defense plan does not argue that Britain keep solid permanent military presence in Japan or Australia. The Labour should bear in mind that the Indo Pacific strategies of France and Japan stretch from East Africa to the South Pacific. Furthermore, she comments that Britain does not necessarily keep military presence to the furthest in the Indo Pacific, but it has to make full use of existing UK facilities in Indian Ocean, ie, the Middle East, East Africa, and Singapore. That would be helpful for the British troop to react to an emergency in the Far East, when China or North Korea defy global rules and norms such as freedom of navigation, territorial integrity, and nuclear nonproliferation in this region. While Shadow Defence Secretary Healey stresses limited budgetary resource, Shadow Foreign Secretary David Lammy does not deny the tilt, but proposes the “three Cs”. That is, Britain should challenge and compete against China geopolitically, but cooperate with them on some issues such as climate change when necessary (“How Labour Can Reform, Rather Than Do Away With, the UK’s Indo-Pacific Tilt”; RUSI Commentary; 14 February 2023). After all, I would argue that Healey’s vison is a sheer denial of Britain’s historical status as a maritime trade nation.

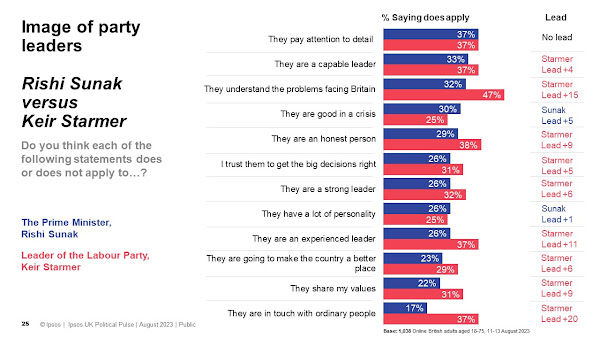

For diplomatic consistency, Britain’s Indo Pacific partners, notably Japan and Australia, need to talk with the Labour shadow cabinet to reconfirm the imperative of the FOIP for global security and common interests in this region. Quite importantly, the general election in Britain is scheduled no later than January 28, 2025, which is quite closely dated to the US presidential election on November 5, 2024. According to the latest opinion poll by Ipsos from August 11 to 14, 56% of UK voters think that Starmer will defeat Sunak in the forthcoming election. While Starmer leads 9 out of 12 points, particularly on being in touch with ordinary people, understanding the problems facing Britain, and being an experienced leader, Sunak leads on being good in a crisis (“Majority of Britons think it is likely Keir Starmer will become Prime Minister”; Ipsos Political Pulse; 24 August, 2023).

The FOIP is multilateral by nature, and Quad members and other regional and global stakeholders need to send a message so that a Labour Britain would not fall into radical anti-colonialist. Above all, Starmer needs to outline a Labour national security strategy, around the world. He told that his cabinet would seek a bilateral security and defense treaty with Germany quickly if he were elected (“UK Labour would seek security and defense treaty with Germany”; Politico; May 16, 2023). But it is not clear how he would adjust Healey’s Euro-Atlantic focused defense and Lammy’s three Cs against China in the Indo Pacific.

The left is not the only problem. Former Chancellor of the Exchequer George Osborne who was an architect of the Anglo-Chinese Golden Era under the Cameron administration, has become a fintech lobbyist to embrace money from China and Russia to the London financial market, after his retirement from politics. Even though David Cameron quit his political career after the Brexit referendum, Osborne remained in the House of Commons as a backbencher. However, he was forced to resign as he was appointed to the editor of the Evening Standard though he was an MP. Ever since he was the chancellor, Osborne wanted to make London a global hub of fintech (“Osborne wants London to be 'global centre for fintech”; Financial Times; November 11, 2015), but his policy was critically concerned, because it seemed that he prioritized the relationship with China at the expense of human rights and US-UK relations. Also, Cameron refused security commitment Britain’s traditional allies in South East Asia when he visited Singapore in 2015 so as not to provoke China (“In for a Yuan, in for a Pound: Is the United Kingdom Making a Bad Bet on China?”; Council on Foreign Relations Blog; October 20, 2015). Osborne also had some dubious ties with Russia, as he accepted donations from a Russian oligarch in 2008 (“George Osborne admits 'mistake' over Russian oligarch”; Guardian; 27 October, 2008). Brexit is a disaster for Britain and the global community, but had Cameron stayed in the office, Osborne would have advanced his pro-Sino-Russian fintech policy at the expense of national security.

As if representing the financial lobby led by Osborne, Sherard Cowper-Coles, head of public affairs at HSBC Holdings PLC, criticized the British government so “weak” as to follow America to curtail business ties with China (“HSBC Executive Slams ‘Weak’ UK for Backing US Against China”; Bloomberg News; August 7, 2023). His remark is “too market-oriented”. Certainly, London has been an offshore financial market where traders can deal with currencies out of American regulation, notably the Eurodollar from the Soviet Union and the petrodollar from OPEC nations. However, the Russian invasion of Ukraine shattered Cold War notions of rational deterrence, and the financial market is required to reject politically risky foreign money more strictly today. Nevertheless, it is quite hard to keep Britain’s open economy, while stopping money laundering by China, Russia, and other revisionist powers (“Why Britain’s Tories are addicted to Russian money”; Politico; March 7, 2022). Regarding the supply chain with China and energy dependence on Russia, Germany and France are frequently criticized, but we have to watch Britain’s handling of these issues as well.

The Sunak administration may not explore the Golden era with China, but the prime minister’s background is business oriented. Having graduated from Oxford University with a BA in PPE, Rishi Sunak acquired an MBA from Stanford University, where he met his wife Akshata Murty whose father is an Indian IT business tycoon Narayana Murty. Sunak himself made his career in hedge fund business before entering politics. In view of his business instinct, he could be tempted to prioritize economic interests with China and take lukewarm attitudes to its threats in the Indo Pacific and the UK homeland, although he declared the end of the Golden Era (“Rishi Sunak: Golden era of UK-China relations is over”; BBC News; 29 November, 2022). Therefore, House Foreign Affairs Committee MPs raised critical concerns with Foreign Secretary James Cleverly, when he visited China at the end of this August. This backlash was led by Conservative MP Alicia Kearns who chairs the committee, arguing that he should have been tough on Chinese espionage in the UK homeland, human rights abuse in Xinjian Uyghur and Tibet, and UK security role in the FOIP operation (“James Cleverly urged to be ‘crystal clear’ with China on ‘the rule of law and human rights’”; Politico; August 30, 2023). Criticism comes not only from Sunak’s party, also from his own cabinet. Minister of State for Security Tom Tugendhat has been a renowned China hawk, and he was banned from entering the country in 2021 (“Cleverly asks Bryant to withdraw ‘Chinese stooge’ claim amid row over Beijing”; Independent; 13 June, 2023). As an HM army veteran, he was so alert to China’s overseas police station in the United Kingdom that he eliminated them, because they were not permitted by the British government (“Chinese 'police stations' in UK are 'unacceptable', says security minister”; Sky News; 6 June 2023).

China appeasers are witnessed beyond partisanship. On the left, there are anti-colonialist wokes. On the right, there are financial lobbyists and their sympathizers. Old fashioned right-left dichotomy is meaningless to analyze correlation of foreign and domestic policy. Britain’s Indo Pacific partners need to be deeply in contact with both ruling and opposition parties to reconfirm security environment in this region and international agreements such as the G7 declaration and the UK-Japanese accord in Hiroshima. Also, it is necessary to reexamine Britain’s own security guidelines like the Integrated Review of Security in 2021, the Strategic Review in 2023, and House Foreign Affairs report led by Kearns this August. Most importantly, Britain’s military presence in Asia would be helpful in the special relationship with the United States, which would ensure a successful Global Britain. At the House of Lords, ex-Foreign Secretary Lord David Owen argued that Americans were more concerned with military adventurism of China than ongoing war in Ukraine, and it would be advantageous for Britain to show its shared security objectives with them in the Pacific (“British carrier in Pacific bolsters US-UK alliance”; UK Defence Journal; September 30, 2023). Though Lord Owen was a secretary of state in the Callaghan administration of the Labour party, his views on the Indo Pacific tilt is completely different from that of current Shadow Defence Secretary Healey. Shadow Foreign Secretary Lammy upholds the “three Cs”, but it is still unclear. After all, it is not ideological label or partisanship, but views and understandings on the Indo Pacific tilt and the Chinese threat that critically matter. Beware of domestic politics in Britain.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment