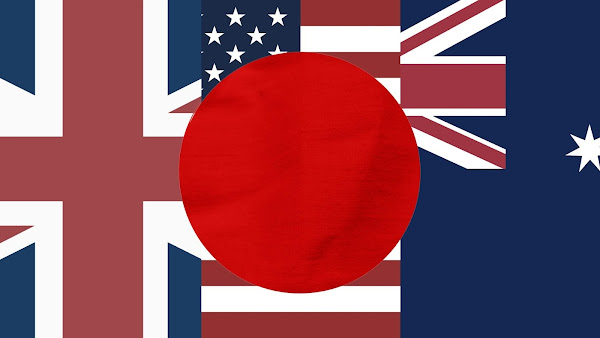

JAUKUS? A Pacific alliance of Japan, Australia, the UK, and the USA.

In the previous post, “Can Britain Draw India into the West?”, I talked about

Britain's joint project of developing next generation stealth fighter with

Turkey, India, and Japan. Geopolitically, the above three were strategic hubs of

the British Empire, and they are located in the west, the central south, and the

east of Eurasia respectively. Of course, Britain is not the hegemonic power

today, but the tilt to the Indo-Pacific area while maintaining ties with Europe

is more in congruent with a global strategic scope of the maritime hegemony in

the past, and that of the United States, the global hegemony today, than that of

a Euro-Atlantic regional power.

It is not necessarily quixotic to explore a geostrategy based on past imperial

experience. There is no denying that Russia's neo-Eurasianist dream to reconquer

Ukraine has turned out catastrophic. On the other hand, Turkey's neo-Ottoman

vision is much more successful to boost its global presence, though this

requires a tight rope diplomacy between the West and the rest. Meanwhile, Japan

is in a mixed position. While aspiring to explore sovereign and independent

initiatives to boost political presence in the world after the Cold War, Japan

positions itself deeply embedded in the Anglo-Saxon security network in the

Indo-Pacific, which is the Quad plus AUKUS, rather than pursuing an imperial

dream in wartime history. Thereby, this country assumes its position as a key

proponent of the liberal world order in this century, which is Pax

Anglo-Saxonica 2.0 against China and other revisionist powers. It would be quite

narrow-sighted to regard Japan just as a tiny insular nation caught between

America and China. From a panoramic view of the world, we understand that Japan

and the Anglo-Saxon hegemony have given geostrategic priorities in the Eurasian

Rimland since the prewar era.

Meanwhile, we have to understand sovereign and independent aspects in Japanese

foreign policy. This July, the Japan Forum on International Relations has

released a new book, entitled "Japan’s Diplomacy in Eurasian Dynamism", which is

a self-portrait of the Japanese strategy in the Eurasia and the Indo-Pacific.

When the Hashimoto administration launched the New Silk Road initiative to

strengthen ties with the Eurasian heartland in the 1990s, it was more like a

romantic exploration of ancient cultural and historical friendship with Asia,

rather than geopolitical consideration. Also, ideological aspects were not so

much important in that initiative. It was the 9-11 terrorist attacks that

prompted the evolution of Japanese grand strategy. Prime Minister-then Taro Aso

publicized the Arch of Freedom and Prosperity against terrorism and autocracy,

in resonance with the Greater Middle East Initiative by the Bush

administration.

Aso's successor Shinzo Abe advanced the grand strategy furthermore. He lead

regional security and free trade initiatives, notably the FOIP and the TPP, when

the United States was plagued with America First isolationism under the Trump

administration. Quite importantly, he called global attention to the threat of

China, particularly from Western leaders. Prior to that, Western media treated

conflicts between Japan and China like Third World regional power rivalries

between India and Pakistan, Iran and Iraq, etc. Actually, I also distanced

myself from those who were obsessed with China in those days, because I was

disgusted with Japan First attitudes of online right wingers and other

revisionists whose vision of the world were hardly panoramic, and sounded

something like Putinistic grudge against postwar Pax Americana and Trumpian

grudge against globalization these days. Without attendance of events at the

Japan Forum on International Relations, I may have missed opportunities to keep

up with the reality of growing challenges by China.

On the other hand, Abe was so wishful as to believe that Russia would return the

Northern Territories in exchange for economic cooperation, as he was poorly aware of

the nature of the Putin regime、which is the rule of power. We should not forget that Abe invited Vladmir Putin to a hot spring resort in his Yamaguchi constituency for a rest just before the bilateral summit in 2016, his attitude to charm

that cruel dictator was something like behavior of a master of a classical-styled Japanese inn at the resort ("Abe and Putin meet at a hot spring resort in Japan"; Yahoo News; December 16, 2016).

For further discussion, I would like to mention the three geostrategic hubs from

historical contexts. Turkey had been a bulwark against Russia’s southward

expansion, and a vital member of NATO and the CENTO to stop Soviet threats in

Europe and the Middle East. India has been a connecting link between East Asia

and the Middle East, and also between the Indo-Pacific and Central Asia since

the era of the British Raj. With such geopolitical background, India has become

an indispensable strategic partner for the United States in the War on Terror

and the Quad today. Meanwhile, Japan has been an offshore outpost to block East

Asian land powers from gaining access to the sea. Currently, Turkey and India

aspire to play independent role in geopolitics of a multipolar world, while

preserving membership of NATO and the Quad respectively. Meanwhile, Japan

upholds the G7 principle of a rule-based world order, which makes this country

reliable for Anglo-Saxon sea-powers.

In addition to geopolitics, it is necessary to mention defense industries of the

three hubs. They have some defense technology, but not advanced enough to make

the whole of the next generation fighter. Turkey exports less expensive and

easily available weapons to developing countries primarily. Notably, the

Bayraktar TB2 drone has won a global reputation, as it helps Ukraine’s

counter-offensive against Russia. However, in advanced technology, this country

needs assistance from major Western powers. Meanwhile, India manufactures

numerous lines of indigenous weapons, such as the Tejas fighter jet, the Arjun

tank, Astra BVR air to air missile, etc, under the “Make in India” campaign by

Prime Minister Narendra Modi ("Top 10 Indian Indigenous Defence Weapons"; SSBCrackExams; October 24, 2020). But since they are not competitive in the global

arms market, India is still dependent on Russia in defense procurement. Through

technological cooperation with the West, India is pursuing self-sufficiency in

national defense.

Unlike the above two, Japan is fundamentally strong in advanced technology, and

provides critical components for Western weapon system. Notably, Japanese seeker

will be integrated with Britain’s Meteor air-to-air missile to make the JNAAM ("Japan confirms plan to jointly develop missile with Britain"; UK Defence Journal; March 4, 2022).

But Japanese defense contractors do not have political network for marketing,

which was quite disadvantageous to compete with France to win the submarine

contract with Australia. Fortunately for Japan, French submarines were edged out

when the AUKUS agreement was declared. Australia switched to American and

British nuclear submarines.

Anglo-Saxon sea powers make their strategies from global perspectives, and the

priority among their regional hubs can change in accordance with the global

security environment. Therefore, it is not recommendable for Japan to bandwagon

with narrow-sighted China hawks in America, in view of current Russian defiance

to the world order through invading Ukraine. They are obsessed with the Chinese

threat in Asia so much that they do not see the world from panoramic viewpoints.

They align with America First right-wingers and antiwar left-wingers to preclude

America from helping Ukraine ("A Moment of Strategic Clarity"; The RAND Blog; October 3, 2022). Also, those anti-interventionists coordinate with

anti-tax movements on this issue ("Inside the growing Republican fissure on Ukraine aid"; Washington Post; October 31, 2022). As mentioned in the National Security Strategy

of the Biden administration, China has become the primary contestant against the

liberal world order. Also, Russia and other revisionist powers obstruct and defy

this world order that Japan rests on its peace and prosperity. Therefore, Japan

should not appear self-interested, through resonating with the wrong

partners..

Under the current geopolitical context, how do Anglo-Saxon sea-powers strike the

strategic balance in Eurasia and the Indo-Pacific? Let me talk about it from

Britain’s relationship with the three joint fighter jet project partners.

For Turkey, The United Kingdom has been the friendliest European nation for decades. Prior to

Brexit, Britain had been endorsing Turkey's bid to join the EU. In the post-Brexit era, Britain and

Turkey need each other more than ever. In trade, Turkey found that a deal with

Britain is more preferable to preserve its economic sovereignty, rather than a

deal with the EU that requires cumbersome procedures of common customs. Quite

importantly, Turkey faced some tensions with the EU, as Erdoğan sent brutal

Syrian mercenaries to the civil war in Libya in 2020, and attacked Kurdish militants in

Syria to stop his claimed terrorism in his country in 2018. However, Britain restrained

to denounce Turkey ("TURKEY AND THE UK: NEW BEST FRIENDS?; CER Insights; 24 July, 2020). India is also a prospective market in the post Brexit era.

Strategically, this country has edged out ex-CENTO but pro-Chinese and

Taliban-tied Pakistan as Britain’s primary partner in South Asia ("The Integrated Review In Context: A Strategy Fit for the 2020s?" Kings College London; July 2021). As stated in

the UK-India joint statement in April this year, their bilateral strategic partnership goes

beyond the Quad plus AUKUS, and even expands to Africa.

Meanwhile, Japan is a key partner in Britain’s tilt to the Indo-Pacific, along

with Australia. As G7 members, both countries staunchly support the rule-based

world order. While Britain needs Japan to over-ride post Brexit political and

economic uncertainties, Japan needs Britain to cope with growing security

tensions with China and North Korea. In trade, Japan endorses Britain’s bid for

the CPTPP. In order to strengthen bilateral security cooperation, Japan launched a joint military

exercise with Britain during the May era, and even partially modeled on the

British system to found its own NSC to enhance the strategic decision-making

capacity ("The UK-Japan Relationship: Five Things You Should Know"; Chatham House Explainer; 31 May, 2019).

On the other side of the Atlantic, the Biden administration outlined American national security strategy

this October, which states that we are in an era of geopolitical and ideological

competition, particularly with Russia and China. According to the publicized

strategy, “Russia poses an immediate threat to the free and open international

system, recklessly flouting the basic laws of the international order today, as

its brutal war of aggression against Ukraine has shown.” Meanwhile, as to China, it states

“[It] is the only competitor with both the intent to reshape the international

order and, increasingly, the economic, diplomatic, military, and technological

power to advance that objective.” On the other hand, it advocates for

international cooperation to resolve globally shared issues climate change,

energy security, pandemics, financial crisis, food crisis, etc. Whether in

competition or cooperation with those challengers, President Joseph Biden is

rebooting America’s global alliance network, while his predecessor Donald Trump

was contemptuous of it. That is favorable for Japan to deepen the alliance via

the Quad.

The strategic emphasis of Anglo-Saxon sea-powers may change, according to their

situational necessity, but Japan is much more advantageous than other fighter

project hubs. Turkey is chronically plagued with the Kurdish problem. Erdoğan

attacked Syrian Kurds, which lead to “NATO’s brain death”. Also, this country

still quibbles about Kurdish asylums in Sweden and Finland, upon their bid to

join NATO. That will place friendly Britain in an awkward position, because it

leads the Joint Expeditionary Force of the Netherlands, Scandinavian and Baltic

nations. India is taken over by Hindu nationalists, and their domestic clash

with Muslims and Christians is an unneligible concern. Quite problematically,

both countries have strong ties with the Kremlin. Turkey bought S-400 surface to

air missiles from Russia. Also, India still abstains from voting against

condemning and sanctioning Russia at the UN General Assembly.

Nonetheless, Japan is free from domestic ethno-sectarian tensions that terribly

inflict on Turkey and India. Regarding the relationship with Russia, current Prime Minister Fumio

Kishida overturns Abe’s appeasement to Putin in the wake of the Ukrainian

crisis. Kishida’s appointment of ex-Defense Minister Gen Nakatani, who is also a

JGSDF veteran, to his Special Advisor for International Human Rights Issues,

sends a strong message that Japan takes human rights as a critical issue of

national security. We can also interpret it that Kishida shall never forgive

brutal crimes that Vladimir Putin committed at home and in Ukraine, and he shall

never make the same mistake that Abe made. In globally

shared issues, Japan has been willing to get involved as a civilian power

in the postwar era through the G7 and various international and regional

channels. The situation and the environment of global security always change.

But whatever happens, Japan should not fall into Japan First, in order to maintain

the reputation and trust from the world.